Toolkit

During the design phase, projects develop suitable data collection instruments to answer their research questions, and define tasks that participants will work on. The design of research tasks that individual participants can complete should be based on the overall research design and project goals. It should involve a plan for the research implementation as a whole, including data collection and analysis, and the role of participants with potentially different skill-sets at different points in the project.

Guiding questions

In designing their citizen science tasks, projects should consider the following questions:

- What resources do you need to implement and run this project, and how will you access them?

- You could look into support or funding programs for citizen science, or look into free tools and resources that you can use.

- What expertise do you have, and what are you missing? How will you fill those gaps?

- This could be by learning about aspects of the project yourself, by finding volunteers or paid services, or partnering with individuals or organisations who can provide them.

- Are there any individuals or organisations you could partner with, and for what purposes?

- You could reach out to researchers at local universities, NGOs with goals similar to yours, or councillors with a political interest in the issue you are investigating.

- Where and how will citizen scientists be involved throughout the project? What contribution can they make? How will you engage with them?

- Citizens could be involved only for data collection, for example by using an app you provide them with; or they could be involved in the entire process, advising the project on key questions and issues.

- What data do you need to collect to answer your research question? How much data will you need? What will you do with it?

- What is the best way to collect the data required to answer the research questions?

- What tools will you use to collect the data? How will you ensure data quality?

The task design includes details for the different kinds of contributions participants can make, and how. Not every participant will contribute at all stages and in all the possible ways to a project. Where and how they engage will depend on their skills, abilities, technology available, and motivation. Therefore, projects need to consider and design their tasks, so that participants with different backgrounds and in different situations can complete them. Task design, or the translation of broad goals into specific actions, requires an understanding of scientific methods and rigour, so the project can produce robust data for their goals.

These guidelines are high-level recommendations for designing and implementing citizen science initiatives developed by the ACTION team. They are based on research findings from within the ACTION project – to find out more, you can read the report of our findings.

- Account for trade-offs

The use of citizen science entails inevitable trade-offs between the quantity of data, the speed at which data is to be gathered and the accuracy of the gathered data. When designing tasks, it is essential to consider and identify which of these factors is to be prioritised and take appropriate steps to safeguard this factor, while taking steps to mitigate threats to the additional trade-off factors. For example, if a project is to emphasise accuracy and quality of data submissions, the task completion time is likely to increase and this can limit engagement. It is important to then streamline and simplify the task completion process to support faster data gathering or take steps to encourage engagement to account for these trade-offs. - Account for technology

It is important to consider the technology and software that volunteers are likely to use to complete your task. Does the task need to support both mobile and desktop devices or is the task designed to be completed outside of the home? Does the task support multiple browsers? Wherever possible, support diverse technologies to lower any barriers to entry. If participants cannot access your task, then they are unlikely to put in the effort to overcome these barriers and continue contributing. If these barriers are technological, it is also possible that volunteers will not be able to overcome these barriers or will not know how. - Provide Context

Citizen science tasks can often be designed and implemented in such a way that they are trivial and simple for volunteers to complete. This is essential for encouraging accessibility and gathering high quality data, but can obfuscate or trivialise their research value, with potential to harm volunteer engagement. Tasks, project resources and educational resources should provide additional context on the value that volunteer contributions pose for the research process. - Provide Feedback

While citizen science tasks are generally designed to be easily understood and completed by all participants, not all projects are able to achieve this. Moreover, even where tasks are otherwise easily understood, participants want and need feedback on the accuracy of their responses and the value of their contributions to scientific research. Providing feedback to participants — either within tasks or through features such as forums or newsletters — can encourage engagement. - Solicit Feedback

Tasks should not necessarily remain static. The design process involves a number of assumptions and trade-offs which may not align with participant expectations. Soliciting feedback from participants is key to ensure the needs of all stakeholders are met, with potential for increased task quality and engagement, as well as volunteer engagement. - Avoid Ambiguity

While the requirements and processes involved within a task may be clear to task designers, these do not necessarily align with the understanding and motivations of volunteers. Support participants through the task process with clear instructions, using discrete, clear questions and limit the need for personal judgement. Consider offering multiple choice answers rather than free text responses, for example. - Consider Time-scales

While citizen science is an effective way to gather large volumes of data for scientific purposes, volunteer engagement is sporadic, asymmetrical and often brief. It can therefore take a significant amount of time to gather larger datasets. This can be offset by focusing on restrictive, limited-time activities such as BioBlitzes, where volunteers are asked to gather or analyse data over a short period of time. While this approach can be very effective, it is less effective for tasks with more longer-term aims such as public engagement and education. It is essential to consider the implications and long-term aims of the approach to be used and which factors are most important — is it essential to gather data quickly or in large quantities? Do the research aims warrant longer term engagement and community building or is one off engagement desirable?

Sometimes the reality of a citizen science – or really any research – project is different from the expectation. Therefore it is important to be flexible while the activities are ongoing, to ensure the main project goal is achieved. However, it is necessary to specify that sometimes the results are more exciting than expected, and they could push the team to plan further activities. It is important to understand the difference between the scope of the current project goals and resources, and possible future initiatives.

TOOLS

Zooniverse

Zooniverse is an online citizen science platform that allows users to classify images or sounds generated by other citizens. The Zooniverse Project Builder is a free and easy to use tool that allows anyone to quickly and easily design, implement and launch their citizen science project. The tool supports four task types and assets including images, videos, text and sound files. If desired, upon completion of the design and beta testing process, projects can be launched to the main Zooniverse website to recruit from potentially millions of volunteers.

Prolific

Prolific is a paid microtask crowdsourcing platform that allows anyone to quickly and easily recruit participants from a diverse, international pool of hundreds of thousands of crowdworkers. It is easy to use and interfaces with a number of common research software packages such as Qualtrics, Gorilla, Google Forms and Survey Monkey. Simply design your study, upload it to the internet and then design and deploy your Prolific task. The Prolific website features a detailed getting started guide and help centre which can help with everything from setting up your task to ensuring data quality. Unlike some other platforms, Prolific enforces a minimum rate of pay, ensuring ethical treatment for crowdworkers, while verifying and monitoring workers to improve the quality of the data gathered by workers.

Citizen Science Project Builder

This is a web-based tool that allows users to develop and implement data analysis Citizen Science projects. It features a web interface that requires limited technical knowledge, and little or no coding skills. It is a simple modular “step-by-step” system where a project can be created in just a few clicks. Once the project is set up, many people can easily be involved and start contributing to the analysis of data as well as providing feedback that will help you to improve your project.

Tutorials

ACTION pilots have developed a range of tutorials to guide their participants through specific tasks:

- Street Spectra has created a tutorial for participants to identify the spectra of common street lamps. It explains how to use the spectrograph they provide together with mobile phones to take pictures of street lamps, and then use the images to categorise the type of lamp.

- Dragonflies and pesticides developed a tutorial to guide their participants – who would already be familiar with counting butterflies or dragonflies on their transects – on how to collect water samples for the project.

- Students, air pollution and DIY sensing developed a tutorial for Air Quality projects in high schools to help others who want to set up air quality measurement projects. It includes an overview of the process they used, and materials developed for workshops and events.

- Tatort Streetlight produced a video of a workshop and slides for education about the effects of artificial light at night on the environment. The video presents a workshop about light pollution, the discussion with the students and the practical part in which the students created ideas for future public lighting. It is a tutorial on awareness increasing and stimulation for finding technological solutions for the protection of insects and environmental friendly roadway lighting. The workshop was held in English, using German slides.

CASE STUDIES

Noise Maps

The project was developed by citizens for citizens, and allowed for several routes to engagement. In workshops with participants, they co-created a data collection protocol, which helped to select points of interest for data collection, and designed their whole data collection process. Participants could further host audio sensors at their home, or engage through guided walks, where they would collect data at specified stops. These different routes were meant to allow citizens with different engagement preferences and available time to contribute to the project in the best way that was possible for them.

Citicomplastic

The project had planned to engage participants in the data collection and results phases. However, due to the pandemic-related lockdown in 2020, they had to adapt their approach. Instead of hosting composters on a farm accessible to a large group of participants, especially disadvantaged youths, they found participants who could host a composter and conduct the experiment in their own backyard. Participants were asked to set up the composter, containing manure and bioplastic, with help from the project team. They then proceeded to take weekly temperature measurements and photos of the decay of the bioplastic.

Open Soil Atlas

The Open Soil Atlas project was developed by the FeldFoodForest initiative: A community project with the goal to plant a food forest garden on an abandoned airport in Berlin. They wanted to regenerate the soil, to bring edibility back to the city, and develop an edible landscape. While they explored the site, they found that they did not have access to data about the soil. Although tests had already been conducted, it was impossible for them as citizens to get access to this data, without going through a cumbersome request process. This motivated them to develop a project that would create soil data that would be openly available. They brought citizens and experts together to brainstorm which data would need to be collected, what their research questions would be, and how the soil data collection protocol should be structured. This helped them create a comprehensive set of information about the soil, while keeping it simple and accessible. They proceeded to put together a solution in the form of the Open Soil Atlas, which is built up by citizens, making both the platform itself and the data freely available to anyone who may need it.

Walk Up Aniene

The Walk Up Aniene project was born in collaboration between organisations, who ran round tables with local committees in Rome to explore the value of citizen science and environmental monitoring. A Sud as an organisation wanted to build the local capacity for citizen science, and develop a citizen science project on environmental monitoring experiences for some time, and was motivated by the ACTION Open Call to develop this idea further. Through their activities they met Insieme Per l’Aniene, who were in charge of monitoring the state of the Aniene Valley Nature Reserve thorugh a river contract, which allows rivers to be managed in a collaborative way with institutions and interested stakeholders. They had already developed a questionnaire that could be adapted for citizen engagement. They joined forces, and developed the Walk Up Aniene pilot together, which was conceived from the beginning as a citizen science project. It is linked with the larger “Roma Up” project, which engages citizens in measuring the water quality of the Tiber.

Citizen science apps

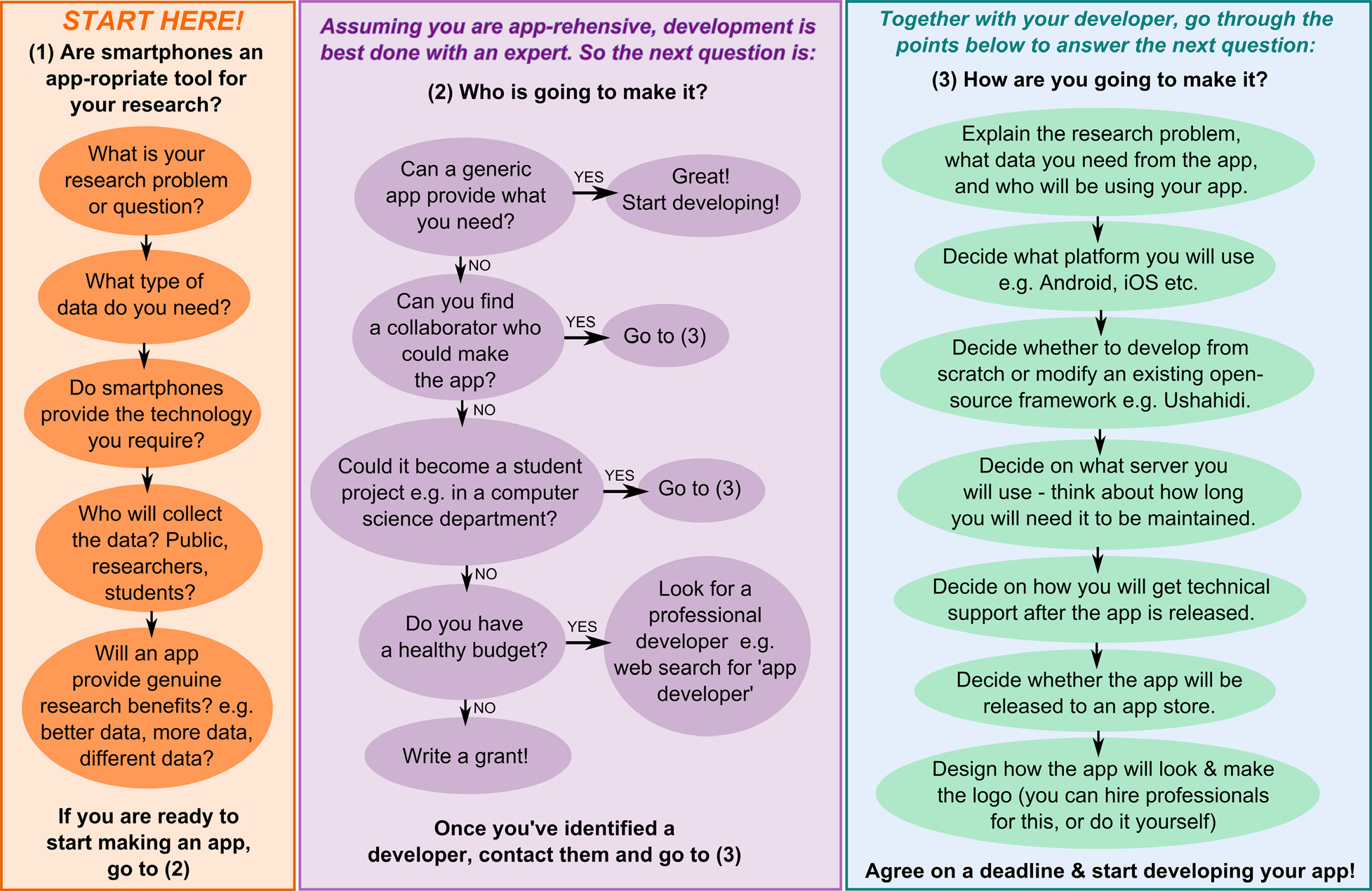

It is important to consider what the best way to engage with your participants will be, and whether a mobile phone app could be a useful tool to use. These decisions must be taken early on, as they can have a big impact on the resources a project needs. While apps can be useful to engage specific target groups, such as younger demographics, both development costs and timelines can be prohibitive. Projects should therefore explore carefully the resources they have, whether there is enough time in their planning to develop a custom app, and the implications for long-term commitment associated with apps, such as the need for and cost of maintenance. If budget and timeline do not allow for a custom app, there may be an app that can support the project’s needs. The below graphic can help projects determine if an app is needed, and what steps they need to take to get to one that fits their needs.

Figure 3: Outline of the development process, by Teacher et al., 2013